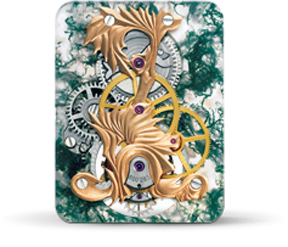

We have gotten a lot of questions from readers about rubies used inside watch movements, so we thought it was high-time to address the issue. Essentially, when a mechanical watch movement is said to have a certain number of jewels in its composition, those jewels are predominantly synthetic rubies created especially for watch movements and used as bearings.

Essentially, the small rubies (also sometimes referred to as jewels) in mechanical movements are used as bearings for the pivots to reduce friction. Being strong and hard, they help to reduce friction and wear and tear amongst the mechanical parts. The advantages of jewel bearings include accuracy, small size and weight, predictable friction, good temperature stability, and the ability to operate over the course of decades.

Essentially, the small rubies (also sometimes referred to as jewels) in mechanical movements are used as bearings for the pivots to reduce friction. Being strong and hard, they help to reduce friction and wear and tear amongst the mechanical parts. The advantages of jewel bearings include accuracy, small size and weight, predictable friction, good temperature stability, and the ability to operate over the course of decades.

These rubies are synthetically developed utilizing aluminum and chromium oxide that undergoes a series of heating, fusing and crystallizing processes (much like synthetic sapphire crystals in the Verneuil process, which we wrote about here). Because the material is mass produced, it does not have the high-cost intrinsic value of natural rubies. The number of rubies used in a mechanical watch varies depending on the complexity of the movement. The more moving parts there are, the more rubies are used. A typical fully jeweled time-only watch has 17 jewels, but watches can have many more than this.

Recently, on a trip to Piaget’s manufacture, I had the rare – and very disconcerting – opportunity to try my hand at setting the miniscule rubies into the designated movement holes. Using tiny tweezers and a microscope, I proceeded to drop a ruby, flick a ruby and eventually get a ruby into its designated spot – upside down! Setting rubies – like the entire act of hand creating a fine watch caliber – is no easy feat.